Disclaimer

The Dover Public Library website offers public access to a wide range of information, including historical materials that are products of their particular times, and may contain values, language or stereotypes that would now be deemed insensitive, inappropriate or factually inaccurate. However, these records reflect the shared attitudes and values of the community from which they were collected and thus constitute an important social record.

The materials contained in the collection do not represent the opinions of the City of Dover, or the Dover Public Library.

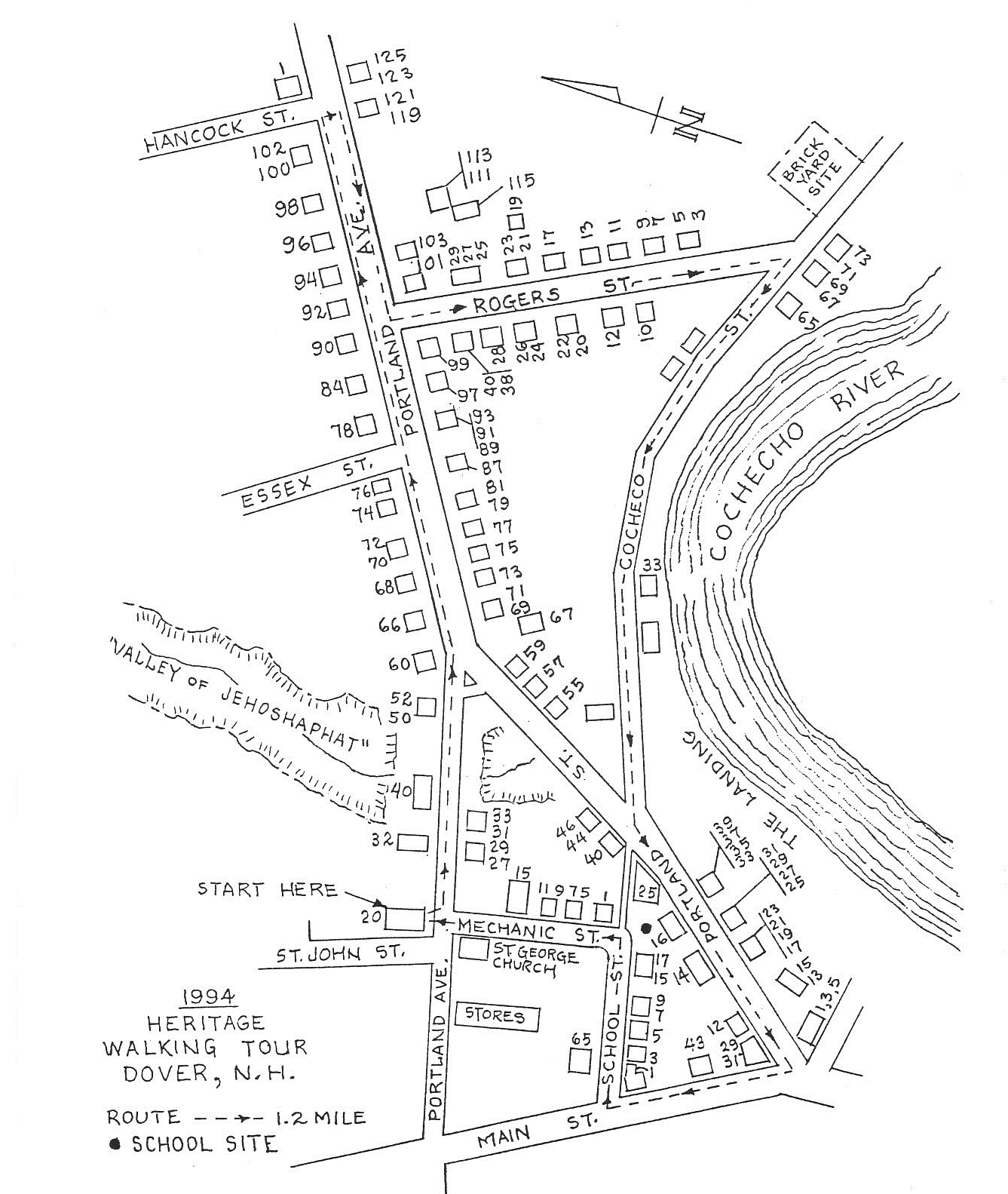

1994 Heritage Walking Tour

Heritage Walking Tour Booklet October 1994 by the Dover Heritage Group, Dover, NH, c. 1994.

In 1978, a group called Dover Tomorrow formed to promote the growth and prosperity of Dover. A subcommittee was tasked with promoting “appreciation of Dover’s heritage”. The Lively City Committee created the first Heritage Walk the next year. It was so popular that new tours were created every year, and held through 2007. By 1982, Dover’s historical society, the Northam Colonists, had taken over the research and creation of the Heritage Walking Tour Booklets. The information on the page below is a transcription of the original Heritage Walking Tour Booklet. The Library has a complete set of the Heritage Walking Tours if you would like to see the original booklets.

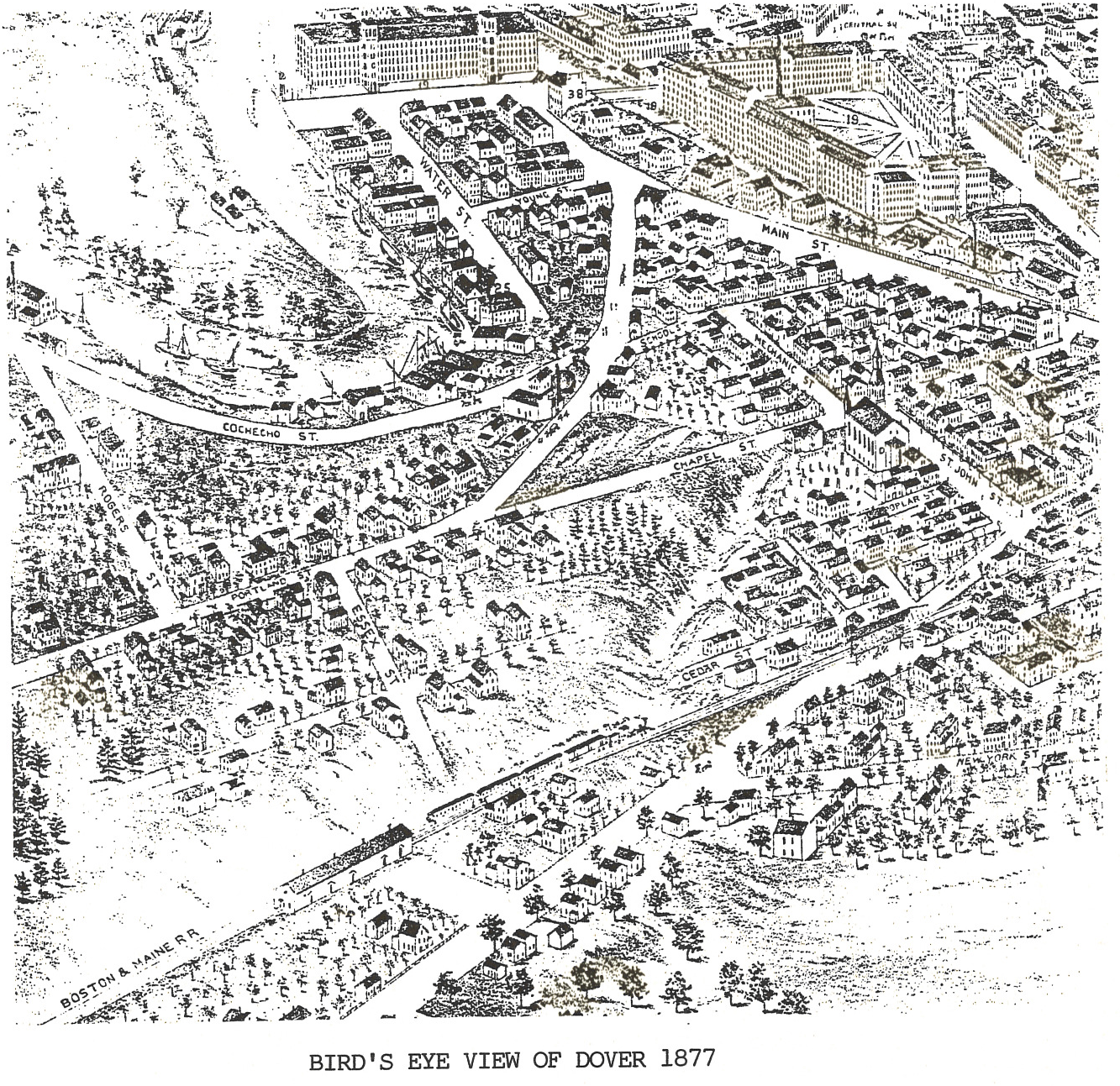

The neighborhood featured in the 16th Annual Dover Heritage Walk is bordered by Portland Avenue, Rogers, Cochecho, Main, School and Mechanic Streets. This area was a prominent residential and commercial hub whose focus centered on activities at The Landing. The neighborhood’s residents were merchants and entrepreneurs, sea captains and dock workers, factory hands and industrialists. Many of the homes atop the hills crowning the riverbanks were grand dwellings with commanding views of the bustling port on the Cochecho River.

Our starting point is the old St. John’s Methodist Church. Now an elderly housing complex, this brick edifice was built in 1876. It replaced a smaller wooden church that had served parishioners since 1825. The cornerstone was laid Oct. 2, 1875 and the church was dedicated Sept. 6, 1876. The entire cost of the building with furnishings was $35,700. In the late 1960s, the sanctuary was declared unsafe and for a while, church services were held in the basement. In 1970 the Methodists moved to their new church on Cataract Avenue and the basement here was used by some small manufacturing companies. The Dover Housing Authority acquired the building, restored and renovated it and it reopened in 1982 with thirty apartments for seniors.

Adjacent to St. John’s is the Waldron Cemetery (1675—1923). Major Richard Waldron, Dover’s infamous 17th century commander, and members of his family are buried here. Waldron was killed by Indians during the June 1689 Massacre at Cochecho. There are some good examples of early 19th century gravestone art in this small cemetery.

In the middle of what is now Portland Avenue, just next to the cemetery, was the home of John Burns. The street was then called Chapel Street and it ended at the Burns’ doorstep. John Burns was among the first of the Irish immigrants to Dover, arriving here around 1820 with his wife Mary Stark (niece of N.H. General John Stark). Burns was a skilled weaver for the Cocheco Manufacturing Company until 1837 when he quit to open a general store with his son Patrick. Patrick Burns was later appointed Dover postmaster by Pres. Buchanan in 1857. John Burns was instrumental in the founding of Dover’s first Catholic Church, St. Aloysius (now St. Mary’s) in 1830. He died in 1874.

Around the time of John Burns’ death, his home was moved sideways and backward so that Chapel Street could be extended eastward to meet Portland Avenue. Patrick Burns’ widow, Nancy Clancy Burns, lived in this home until her death in 1917 at the age 95. The house was torn down, probably in the 1920s.

Chapel Street had always been a dead-end street due to geography. The Valley of Jehoshaphat, a huge ravine through which ran George’s Creek, stretched from the B&M railroad tracks (Near Red’s Shoe Barn today) to the Cochecho River. No roads or bridges crossed its deep crevices, severely limiting development on Dover’s east side and hindering access to town for those who did live in that area. Residents had to either travel down the Turnpike (Portland Ave.) to Cochecho Street and then up Main, or go further east to Oak Street and across to the northern end of Central Avenue.

In the early 1870s, civil engineer Benjamin Collins, owner of the property bordering the ravine at 60 Portland Avenue, started encouraging citizens to dump their garbage into the Valley of Jehoshaphat, filling it in with personal refuse and discarded junk. Some restrictions were posted, but over the years there were many infringements. By 1875, the gorge (now referred to as “The Dump”), had been filled in enough that a carriage road was put in and a plank sidewalk extended from St. John’s to Collins’ property. It was a welcome shortcut to town and much appreciated by east side residents.

Portland Avenue was originally called The Turnpike. The road opened ca. 1805 and there was a tollgate at Oak Street. The Turnpike became a free road in 1840. In the 1830s there were only about a dozen homes along this road; by 1851 sixteen houses existed. But after the Valley of Jehoshaphat was filled in, development was swifter. New streets such as Essex, Forest, and Hancock were created and by the early 1890s dozens of new residences had been built here. And because of the proximity to the river, most occupants had ties to the shipping and the sea.

The properties at 32, 40 and 50-52 Portland Avenue are sited on land originally part of the brick homestead at #60 which was built ca. 1820-25 by Joseph Smith. Smith (1771-1857) came to Dover from Massachusetts in the early 1790s and started a bakery at the Landing. By the early 1800’s he had purchased large parcels of real estate in our walk area and had expanded his business ventures to importing and exporting merchandise of all sorts. The economic Panic of 1828 nearly brought Smith to financial ruin. Much of his property was seized by the banks and held in trust until his debts were repaid. He survived these setbacks, however, and continued in business for years afterward. His obituary stated, “Few men have been more distinguished for industry and perseverance in business, or have added more to the wealth and prosperity of the community.” Benjamin Collins was the next owner of #60 from 1868—1906. The home next passed to Alvan Place and then to Frank J. Grimes. Present owners are retired N.H. Supreme Court Justice William Grimes and his wife, Barbara T. Grimes.

On the other side of the street, nearly all the land on Portland Avenue from the intersection with Cochecho Street up to Rogers Street was owned by Daniel Waldron, descendant of Major Richard Waldron. In 1812, just over an acre along the hill now Portland Street was sold to Jonathan Robinson for $150. In 1819, Waldron sold the adjacent 2-acre parcel to Robinson and Andrew Peirce for $300, and the third lot (over 3 acres nearest to Rogers St.) sold to Capt. James B. Varney for $327.50. Waldron’s land, therefore, covered the area for all the houses from 55-59 Portland St. and 67-93 Portland Avenue.

It should be noted that somewhere in this third lot was located the garrison of Thomas Paine during the 1600s. The area was called Rawling’s Mount and its exact location and reason for its disappearance are unknown today. Just west of these Waldron lots, in the triangle of land between Cochecho and Portland Streets, a distillery operated from the 1820s to the 1850s. Several other historic properties still exist on Portland Avenue. They include:

66 Portland Ave.—Judith Plumer bought this lot from the Cocheco Mfg. Co. in 1837. In 1849, Mary Plumer sold the land and buildings to Martha Robinson who, in turn, sold it to Eli Grant in 1854. Grant was an overseer at the Print Works and the family remained here until at least 1933.

68 Portland Ave.—In 1831, brothers Nathaniel and Jeremy Young, owners of wharfage and a tannery at the Landing, sold this land to Nathaniel Ela, proprietor of Ela’s Tavern near the corner of Washington and Main Streets. In 1835, Ela sold to Andrew Peirce III. The home was built ca. 1835-40. In 1847, it passed into the hands of James H. and Hannah M. (Place) Hanson. Their son, Burnham Hanson, acquired it in 1868 but never lived here (he was a Mechanic St. resident). After Hanson’s death, it was left to his niece Abby K. Ford.

69-71 Portland Ave.—Capt. Andrew Peirce, Dover’s premier mariner, built this homestead here before 1827. In 1840, his son Andrew Jr. sold the home to Ebenezer Faxon. By 1867, carpenter John Leathers lived in #69 and about 1880 sea captain George Drew moved into #71 as did Lizzie Drew, a teacher. Sometime during these years Daniel Trefethen (1801-1886) owned this house also. Trefethen lived at 67 Portland from 1831 and was another renowned sea captain. That house was razed ca. 1970.

73 Portland Ave.—Another home belonging to Capt. Daniel Trefethen, this house was sold after Daniel’s death to Walter T. Perkins in 1887. Perkins didn’t live here however; his home was next door at #77.

76 Portland Ave.—Built early in the 19th century, this house was the residence of Capt. William Trefethen whose brothers also lived nearby. William was a packet and gundalow captain who brought the first ton of coal into Dover via the Cochecho River. In the 1890’s, box-maker Joshua Trefethen sold the property to Charles T. Henderson. Essex Street was originally Smith’s Lane (a cow path to Joseph Smith’s pasture). The street was broadened in 1871, “the sidewalk on the west side taken from Capt. William Trefethen’s garden plot.”

77 Portland Ave.—In 1822, Andrew Peirce sold this lot to Charles and Ezra Green. Walter Green sold it in 1849 to the Farmers and Mechanics Steam Mills Co (of which Andrew Peirce III was treasurer) who sold it that same year to mason David Wilson who lived here until 1876. In 1878 machinist Augustus Perkins moved in and from 1882—1900, Walter T. Perkins, who was in the steam and gas heating business, lived here.

78 Portland Ave.—Another Trefethen, Daniels’ twin brother Archelaus, lived here. Also a packet captain, Archelaus Trefethen’s vessel was the “William Penn.” The family owned the property until 1886. The Dame family lived here off and on in the 1870’s and 80s. John Dame was a city councilor and served as Fire Chief in 1871. However, his son John Edward became more prominent when, in 1909, he shot and killed his father-in-law, police officer Walter S. Sterling at Sterling’s 133 Portland Avenue home. Many people recall the Panapoulos’ neighborhood store that was here until the mid-1980’s.

79-81 Portland Ave.—This home dates to 1874. It was built by Ezra Twombly who was the Register of Deeds for a number of years. His widow Lucinda lived in #79 until around 1900.

84 Portland Ave.—This was the home of James McDuffee and his heirs for nearly 110 years. The family was a politically active one: Lyman was a Ward 2 Councilman and later served on many city committees.

87 Portland Ave.—In 1846, Jonathan Richardson sold the land here to brick makers John and Amos Sargent who probably built this home. Dry goods merchant George K. Nealley owned it from 1865-71. The next owner was Leonard Rand of the Whitney Rand Co. This company made the Dover Egg Beater under the name of the Dover Stamping and Mfg. Co. Water works superintendent Willard Sanborn owned the home from 1888—1905. Bernard O’Kane, who had a neighborhood store on Broadway, was here from the 1930s to the 1960s.

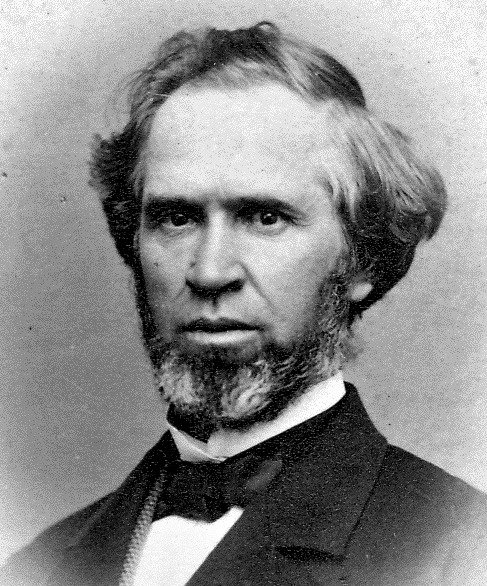

George K. Nealley

89-93 Portland Ave.—Capt. James Varney built this house prior to 1827. His occupation was wood and lumber surveyor. Family members occupied the home until 1890, then the Edward Thompson family owned it until the 1930s.

90 Portland Ave.—A Mrs. Hutchins lived here in 1871. Later, this home belonged to Leonard S.R. Gray, a Civil War veteran. In 1905, the Redfield family moved here from Haverhill, Massachusetts. It is possible that Anne Redfield was engaged to marry Walter Sterling at the time of his murder. In 1909, after the murder, the family moved away and was never heard from again.

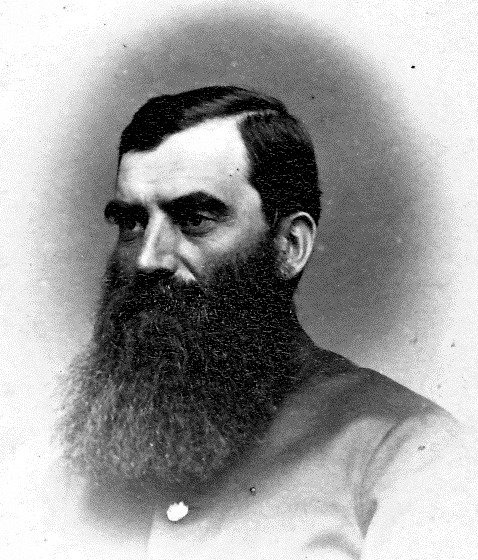

Leonard Gray

92 Portland Ave.—In the 1880s, this was the home of Marshall B. and Minnie Hammond. Marshall was co-owner of the Converse & Hammond Lumber Company at the Landing. His father, Moses, became a partner in 1889 when Joshua Converse retired. Marshall helped his father run the business until his death in 1898.

94, 96, 98, 100-102 Portland Ave.—These four properties were originally owned by the Guppy Family. They were built in the 1870s as tenement houses. In 1910, Jeremy Belknap Guppy donated these homes to area churches: #94 to the Peirce Memorial (Universalist) Church for use as a parsonage, #96 to the First Parish (Congregational) Church, #98 to St. John’s Methodist, and #100-102 to the First Unitarian Society. J.B.Guppy died in 1917 leaving his home (which dated from 1690) and a large tract of land to the City of Dover for the “express purpose of a public park.” Today, Guppy Park is the result of his generosity. Hancock Street was originally on Guppy land. In 1880 there was a land dispute which eventually conceived Hancock and the extension to Forest Street. Guppy was a zealous Democrat and he named the street for Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock who was running against James Garfield and Chester Arthur in the 1880 presidential elections.

97 Portland Ave.—George and Nettie Colby sold this house to Samuel S. Lock in 1868 for $225. Samuel was a carpenter who also ran a neighborhood store here. In 1900, he moved to Berwick Junction.

99 Portland Ave.—Ebenezer Faxon bought this land at an 1844 auction of Robert Rogers’ property. Faxon sold in two lots in 1867 to George M. Colby (now #97 and #99). The following year Colby sold this home to Charles T. Henderson for $1000. Not six months later, in 1871, Henderson sold the home for $1300 to Augustus T. Coleman. Coleman was originally a sea captain but later gave up the sea to enter the grocery business with his brother-in-law Charles H. Cushing (Coleman and Cushing on Central Ave.). The Cushings also lived here at #99. Coleman died in 1897 and Cushing in 1918.

Ebenezer Faxon

101 Portland Ave.—This home was built ca. 1860 by Samuel Howard Henderson whose second wife was Sarah Ann Guppy, granddaughter of Capt. James Guppy. Samuel died in 1867, but his widow Sarah lived here until her death in 1900. Charles T. Henderson (#99 Portland and later 13 Rogers St.) was their son.

111-113 Portland Ave.—This duplex was owned, in 1871, by John Rines and George W. Colbath. Colbath was Warden of the State Prison at Concord for many years and Rines was city assessor. Their property extended a long way back to the Horne (later Chesley) Brickyard.

Rogers Street

There are two versions of how Rogers Street got its name. One claims that Henderson’s Lane, as it was originally called, was renamed Rogers Street by John P. Hammond for his Eliot relatives, Willis and John Rogers. The other version says the street was named for Capt. Robert Rogers who owned a home on Portland Street. In any event, ca. 1840 the lane was extended over the sand banks belonging to the brickyards at the lower end of the hill to meet Cochecho Street. Samuel Henderson and Samuel Cushing were two of the major landowners during this period. Historic homes on Rogers Street include:

28 Rogers St.—Charles Cushing built this home for his residence in the 1880s. After his death in 1918, his widow Lydia sold the house to James Upham but she continued to live here, renting from Mr. Upham until she died in 1936.

24-26 Rogers St.—This duplex was also built in the 1880s by Charles Cushing. Both lots at #28 and #24-26 were bought by Charles’ father Samuel ca. 1843 from Capt. Robert Rogers. After Rogers’ death in 1844, more parcels on Rogers Street were sold at public auction to pay off $4000 in debts owed by the captain’s estate.

21-23 Rogers St.—Until the 1860s, about half the land on the northeast side of Rogers was owned by Samuel and Sarah Henderson. In 1862, Andrew J. Roberts, a clerk in G.L.Folsom’s paint store, purchased this lot and soon built a home here. The store was now Folsom & Roberts and was located on Chapel Street. Rogers died in 1902.

20-22 Rogers St.—Samuel Cushing lived here from the mid-1830s. The house was said to have been used as a lighthouse, the occupants having hung lanterns in the attic windows to guide ships up the Cochecho River. Mr. Cushing worked as a house carpenter until his death in 1865. His son Charles and daughter-in-law Lydia lived here also until moving to their new home at #28.

17 Rogers St.--$200 bought carpenter John P. Hammond this house lot from Sarah Henderson in 1862. The home probably dates from 1865. Hammond’s later occupation included work at the glue factory Wiggin & Stevens. He died ca. 1880, but his heirs lived here well into the 1940s. They included wife Susan, and children Carrie, a schoolteacher, and Willis, a plumber.

13 Rogers St.—Augustus T. Coleman purchased this land from Daniel Trefethen in 1861. Both men were Dover sea captains. The Colemans lived here until 1870 when they traded houses with Charles T. Henderson (son of Samuel) who lived at 99 Portland Avenue. In 1878, Coleman joined his brother-in-law Charles Cushing in a grocery partnership. This house remained in the Henderson family until 1920.

12 Rogers St.—In the 1830s, the home here was one of two original dwellings on this street (along with the lighthouse at #20-22). Brick maker David Sargent was the original owner. He sold #12 and the land where #10 is now to Samuel Cushing in 1838. The original #12 was probably torn down by Mr. Cushing and the house here today built ca 1870 by Cocheco Mfg. Co. worker John M. Clark. The Clark family owned it until about 1950.

11, 7-9, 3-5 Rogers St.—In the 1860s this was the site of Bennett & Roberts brickyard. It was sold in 1869 to George W. Horne and his son Gustave. Although Gustave died in 1873, and George Horne in 1890, the firm of G.W.Horne prospered until its sale by Charles Horne to Charles P. Chesley in 1897. The brickyard continued under C.P.Chesley at 76 Cocheco Street and operated until about 1920 when Chesley became a real estate and farm agent. Of the three rental units that are here today, Chesley probably built #3-5 and #11. The middle house, #7-9, was moved onto Rogers Street from its original site across from the Sawyer Block on Main Street. It was built originally in 1791 and belonged to an Amos White who sold it to the Dover Manufacturing Co. in 1824.

Gustave Horne

Cochecho Street

Cochecho Street was originally called Flagg Road, named in 1821 for Capt. William Flagg (1770--1844), another Dover deep water sea captain. Flagg built his brick mansion, Tidewater Farm, along the banks of the river ca. 1815 and insisted that this road be laid out so that he could have a shorter route home. As he was Dover’s wealthiest citizen at the time, his wishes were quickly heeded. In 1830, the street was renamed Cochecho.

Tidewater Farm

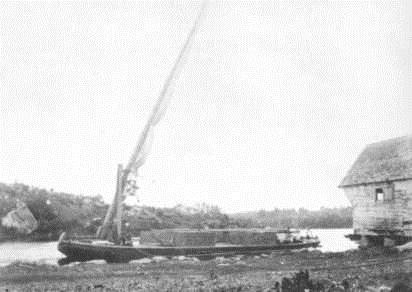

During the 18th century, development was slow along the river, but every citizen’s existence was tied to its waters. Gundalows carried raw materials and finished goods back and forth to Portsmouth and the population of the “Village of Cochecho” gradually grew to the same size of that at Dover Point. Dover boatyards built small schooners and enterprising men like Michael Reade made fortunes in the lumber business. But the riverbanks here were mainly used for storage of cargo and cordwood until 1785. In that year, town selectmen voted to sell and/or lease lots bordering the Landing (around what is now the back of the old Clarostat mill.) By the end of the 18th century, Dover Landing had a bakery, a tavern, retail stores, a clock maker, a newspaper (The Sun), a distillery, a tannery, a hardware store, and a dram shop.

By 1810, ten gundalows were in constant use on the river. Each could carry over 30 tons of cargo and could come up to the Landing at half-tide. Over a dozen brickyards were prospering, using the good clay from the riverbanks here and firing their kilns with the 30,000 tons of cordwood that were delivered annually. Small packets (keel boats 30-40 feet in length) also sailed regularly to Portsmouth, Portland, and Boston, although they could only reach Dover Landing at high tide. They carried light freight and passengers.

In 1815, Joseph Smith and partners built the first brick block of stores on the Landing on the east side of Main Street and during the 1820s, with the construction of the huge cotton mills, Dover’s population nearly doubled: from 2871 in 1820 to 5449 in 1830. In 1823, an Aqueduct Company was chartered to supply fresh water to homes surrounding the Landing, and in 1824, a group formed to investigate digging a canal from the Landing to Lake Winnipesaukee. (The $700,000 cost was too prohibitive.)

By 1825, Dover was the second largest town in New Hampshire (behind Portsmouth). Dover shipyards produced as many as six vessels a year ranging in size from 30 to 600 tons. In 1835, Rogers and Peirce launched a 300-ton ship from the yard on the Landing. But, that same year, all these competing shipyard owners and packet captains joined forces in a new conglomerate called the Despatch Line of Packets. They had all heard rumors that the railroad would soon be coming to Dover and thought the consolidation of their operations would be the best move.

The Dover Despatch Line of Packets commanded seven 50-80 ton vessels on regular routes to other east coast cities. All could dock at the Landing at high tide as they only drew 7-8 feet of water when fully loaded. Vessels drawing 10-11 feet could come to within one mile, while those drawing more than 17 feet could only come up to a point 2.5 miles from Dover wharves. Gundalows were then used to unload or “lighter” these ships upriver. The time-consuming extra step added to inconvenience and expense of shipping to the port of Dover.

Gundalow

Yet, in 1840, the Landing’s prosperity was at its highest peak. Nearly 200 vessels (not counting gundalow traffic) came in to Dover. The Cocheco Mfg. Co. switched from wood to coal to fire its boilers and erected huge coal sheds on the Landing (site of Public Words garage now). The value of goods shipped just between Dover and Portsmouth was $2.4 million that year.

However, on June 30, 1842, the Boston and Maine Railroad finally made its connection into Dover and opened a station on Third Street. Here was a means of transportation not dependent on weather or tides and boasting of modern conveniences and regular schedules of delivery. Shipping declined rapidly in the 1850s and 60s.

The Dover Gas Light Company organized in 1850 and located their gasworks at the old distillery site. In 1868 they offered to share expenses with the city in clearing out obstructions near Landing wharves. The Dover Board of Trade got involved and in 1871, the first federal funds for dredging ($10,000) were approved by Congress. During this decade, the Narrows was widened and the Gulf was deepened to 10-14 feet depending on the tide. Shipping to the port of Dover gradually increased once again and dredging funds continued to be appropriated.

In 1877, The Dover Navigation Company was organized by an ambitious group of local businessmen looking for a profitable investment. They saw the resurgence in commercial shipping by schooner and knew the industrial and mercantile needs of Dover. They decided to build a vessel capable of hauling large cargoes, particularly coal, right into downtown wharves. The “John Bracewell,” a three-masted schooner 113 feet long and 29 feet wide, was built in Bath, Maine for $13,000. It was launched in 1878 and the ship could carry 350 tons. It met with immediate success and more schooners, each larger than the last, quickly followed. By 1889, the Dover Navigation Company owned ten schooners, two of which were too large to ever dock in Dover! But on Dec 7, 1888, Dover people did get to see the “J. Frank Seavey” at the Landing. The vessel was 144 feet long and 34 feet wide and carried 600 tons of coal. She was towed into port by a tug and the local newspaper boasted, “The vessel is a beauty…[with] the largest cargo that ever came…without lightering. This shows that this is the vessel for the port of Dover.”

The renaissance of Dover shipping in the 1870s-1890s led to much industrial development along the Cochecho River. The Dover Gas Light Company, which had begun operations in 1850, constructed a bridge in 1874 over the street from the gasworks to their wharf for transporting coal from the vessels in harbor. In 1891, the company was leased for twenty years to the United Gas & Electric Company and in 1905, became known as the Interstate Gas & Electric Company. In 1909, they merged with Twin State Gas & Electric and in 1914, Twin State “absorbed all previous light and power interests in the city.” The foundations of the gas works can still be seen and Public Service of New Hampshire occupies the old power plant.

Other important Cochecho Street businesses included:

Wiggins & Stevens—89 Cochecho St.--Organized 1858. Sandpaper and glue-making. 8 employees. They imported sand, flint, and quartz. An 1873 fire destroyed the factory but it was rebuilt. By 1890, they manufactured only glue (60 tons/yr.) which was shipped to a Malden, Mass. sister factory for use in making emery, sand, and match papers.

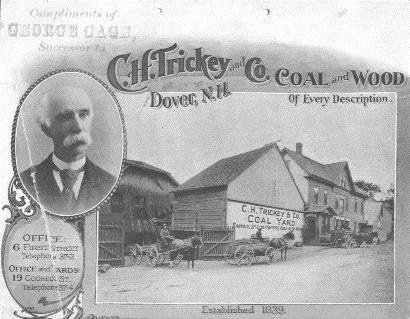

C.H. Trickey Coal Company—19 Cochecho St.--Organized 1872. Coal. 20 employees & 16 horses. Charles Trickey bought the coal business from Moses D. Page and in 1876 enlarged the coal sheds and expanded to six pockets along the river. This company did all the hauling for the Cocheco Mfg. Co. They could store 4000 tons of coal at the Landing and they annually sold over 10,000 tons. Trickey was a founder of the Dover Navigation Company and their second schooner was named for him in 1879.

D. Foss and Son—Portland St.—Organized 1874. Wooden packing crates. 75 Employees.

Dennis Foss and son A. Melvin came from Strafford and opened their wooden box factory at the site of the old N.H. Flax Mill. They also sold grain and later added the manufacture of doors, sashes, blinds, stair posts, rails, bobbins and spools. But primarily, Foss provided all the packing cases for all the cotton cloth and shoes being exported from Dover.

Converse & Blaisdell—17 Cochecho St.—Organized 1874. Lumber. 50 employees.

Joshua Converse supplied lumber, lime, cement, plastering hair and pipe. In 1878, the company became Converse & Hobbs, then in 1883, Converse & Wood, and in 1884 Converse & Hammond. In 1889, Converse retired and A.C. Place joined Moses Hammond. By 1891, A.C. Place was the sole owner, but the factory was still known as Converse & Hammond. In 1898 the name was changed to A. Converse Place Lumber Co. Their annual output was 4-5 million feet of lumber and their wharfage covered six acres at the Landing. They also sold stone, slate, firebrick, interior mantels, guano, fertilizers, and dried bone.

Valentine Mathes—Cochecho St.—Organized 1879. Grain, groceries, straw, hay. 15 employees.

Mathes began on Folsom Street in 1879 selling groceries. In 1881, he moved to the Landing, acquired wharf space and built a 50-foot coal pocket on Cochecho Street. His store sold flour, grain, groceries, coal, wood, shingles, clapboards, straw and hay. Mathes retired ca. 1900.

Valentine Mathes

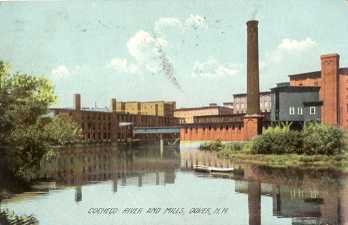

Cocheco Manufacturing Company. Organized 1821. Cotton cloth, calico. 2000 employees.

And foremost of all the businesses was the Cocheco Mfg. Co. whose construction and growth made Dover a bustling city. This giant, in fact, kept these other tradesmen in business: it got its crates from D. Foss, its employees bought groceries at V. Mathes’ store, power was supplied by the Gas & Electric Company, lumber for construction came from Converse & Partner, and coal for its boilers was brought in by Trickey. The Cocheco Mfg. Co. had its coal storage sheds on the south side of the river and owned several factory shed and workers’ houses on Cochecho Street.

During the 1880s it was not unusual to see eight or nine schooners in port at one time. Dredging operations continued with the goal being seven feet of depth even at low tide. By 1895, over $164,000 had been spent dredging the Cochecho River and the future appeared bright. But on March 1, 1896, a late winter storm ravaged Dover with an intensity never before seen in the seacoast. Christened “Dover’s Black Day,” the storm’s driving rain caused the river to rise 6-10 feet. Hugh ice flows broke loose up river and crashed into Dover’s bridges. Three were destroyed. One-third of the Bracewell Block, (Farnham’s today) fell into the river.

Bracewell Block

Nine carloads of lumber were washed off wharves at the Landing and 1500 barrels of lime ignited an uncontrollable blaze. Immediate damage was $300,000. But worse, all the sand, silt, and debris that flowed over the dam lodged in the dredged out areas of the Cochecho River. All the work that had been completed from 1835 to 1895 was now undone in a single day. Sixty years worth of improvements were lost and the Landing never recovered.

17 Portland St.—Schooner House—Recently restored, this ca. 1780 colonial was home to the Young family. Nathaniel and Jeremy Young operated a 250-foot wharf “with water deep enough to accommodate any vessel that can pass over the Gulf, “ three storehouses, and a tannery with 75 vats. The brothers’ ledger from 1821 shows the diversity of goods that they housed: food, liquor, clothing and fabric, hides, feathers, buttons and yarn, building materials, furniture, books, cigars, gravestones and guns. Youngs’ Warehouse also rented gundalows for $1.00 per day, and as a sideline, the brothers trained dogs. Jeremy drowned in the Cochecho River in 1848 and their wharf properties were auctioned off in 1864 after Nathaniel’s death.

29-31 Main Street—Sawyer’s Block (Krans & Krans)--Hosea Sawyer purchased this lot in 1822 for $715. By 1825, he had completed this graceful building. Its cost was $8,766.26. Sawyer’s Block housed offices and retail establishments and remained in the Sawyer family until around `865 when ownership passed to John L. Platts, a shoe manufacturer who died in 1887. During the early 20th century, Platt’s Block housed Raoul Roux’s Market until about 1920. During the 1940s and 50s, the Elcho Lunch was here. The Last Chance Saloon operated here in the 1970s, and after extensive renovations, Sawyer’s Block was restored to its original appearance in 1980. The law firm of Krans & Krans occupies and owns the building now. The square outside its doors was named Lafayette Square in 1825 when Gen. Lafayette, Revolutionary Ware hero, visited Dover.

43 Main Street---Michael Reade House---This ca. 1780 home is one of the few dwellings of the

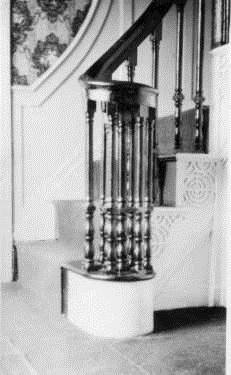

pre-industrial era surviving in downtown Dover. It was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1980. The home’s builder was Michael Reade, Sr, born in 1741 in Kilkenny, Ireland. Reade came to Dover before the Revolutionary War and was one of the town’s first Irish immigrants. Reade was an ambitious entrepreneur who made a great deal of money in Landing real estate speculation and lumber exporting. By 1800, he was the called the “principal merchant” on the Landing. His home is significant for the high quality and detail of its interior woodwork.

Reade House interior detail

Reade’s house represents an era when this section of town was an important commercial center dominated by relatively few substantial homes. Most of these homes were destroyed as the mills were rebuilt and expanded and as worker housing for the operatives was constructed.

Reade’s son, Michael Jr., was born in 1778 and inherited a small fortune when his father died in 1821. Michael Jr. stayed in this house and enjoyed a life of leisure acquiring a reputation as a storehouse of local history. He was described as a man who “kept away from temperance meetings and antislavery lectures and rarely went to church.” Michael never married, “rarely smiled, never laughed.” He objected strenuously when ledge on Main Street was blasted in the 1830s to lower the steep grade, ultimately requiring him to climb six steps to his front door. He is said to never have walked on a sidewalk in Dover from that time until his death. He lived frugally here with his sister and “refused to buy butter when the price rose over $.25 a pound.” From 1812 until his death in 1864, he kept Interlinear Almanacs which recounted ship arrivals, Landing events, weather, and some political and economic commentary about the Dover of his day.

School Street

School Street was named for the 1810 one-story wooden schoolhouse that was located here. It was originally known as the Landing School and sat on the south side of the street where today the walking path starts down the hill. The street was a traffic thoroughfare connected to Cochecho Street until 1989 when the path was substituted.

The Landing School was replaced in 1828 by a two-story brick structure. In 1883, the school was renamed the Sherman School in honor of Enoch S. Sherman who became its headmaster in 1837. Under Master Sherman’s leadership, the school became one of the best in the state. In addition to the usual school subjects. Sherman taught surveying, algebra, astronomy, philosophy, bookkeeping, and chemistry. His salary was $35 a month. The Sherman School was damaged irreparably in the Hurricane of 1938 and had to be taken down.

Although it is difficult to imagine now, the houses on this block were substantial residences with significant architectural style and detail. Few examples remain:

65 Main St./2 & 6 School St.—Solomon Jenness House—Restored in 1991 by Edward George, this massive brick home now houses Cellular One. It was built by Deacon Jenness in 1821. In 1856, the land and buildings were divided into two properties owned by two brothers, George and Daniel Wendell. George was a dry goods dealer and Daniel was Solomon’s son-in-law and an insurance agent. Daniel Wendell died in 1895 leaving the west side to his daughter Caroline. She sold it in 1901 to Dominick Durkin, a saloon owner. The east side of the house stayed in George Wendell’s family until it was acquired by Edward George in 1968. Mr. George died in 1991 and the property is now owned by the Edward J. George Family Trust.

Solomon Jenness

15-17 School St.—Mason Samuel Ham bought this lot in 1825 from Stephen Evans and built this home soon after. Samuel died in 1869, but his widow Mary lived here until 1885. The house stayed in the Ham family until 1923. From 1923—1971 the Janetos family owned, but did not reside at, this house. One occupant was Vasilious Kumutsos (1935-1955) who ran the Manhattan Café on Main Street. (The café was razed in 1967 for the Janetos Shopping Plaza.)

Mechanic Street

On Mechanic Street also existed an important residential neighborhood during the 19th century. All of the houses on the west side of the street are gone, and just a few remain on the east side. These include:

5-7 Mechanic St.--This house was owned by Theodore Littlefield who lived at 15 Mechanic from 1825--66. It passed to his widow, Susan who, in 1907, left #5 to the Washington St. Baptist Church and #7 to Abbie Hagan. In the mid-1920s, Nicholas Skaltsis acquired the property and the Skaltis family lived at #7 until 1945. Peter Athas, proprietor of Peter’s Fruit Store near the Central Avenue bridge, lived at #5 from 1931—45. In 1972, the home was sold to George Mitropoulos.

9-11 Mechanic St.--Boasting one of the most architecturally significant doorways in Dover, this home dates from the early 1800s. In 1867, brothers George and Albert Tash bought this home from a Rochester resident. The Tash brothers dealt in groceries and also manufactured shoes and boots. Albert died in 1870 and George in 1886. At the time of his death, George was president of the Cocheco National Bank. Members of the Tash family lived here until 1905. In 1967, George and Stella Mitropoulos bought the house and moved into #11.

15 Mechanic St.---St. Jean’s Hall--Theodore Littlefield, a Chocheco Mfg. Co. machinist, purchased this house in 1825 and lived here until his death in 1866. His widow Susan continued here until she died in

1907. At the time, Susan Littlefield left the house to a friend, Miss Ellen Young, for use during her lifetime (she died in 1914), and then to the Dover Children’s Home. In 1915, the Children’s Home sold the house for $2000 to the Dover Greek Orthodox Community who converted it to a church and a school. In 1946, La Societe Saint Jean-Baptiste bought the property and also two pieces of property to the north. St Jean’s sold the building to James J. Woods Jr. in 1981.

St. George’s Church---This building was originally the parish hall for St. John’s Church. The money for its construction was donated by Mary E. Lothrop (daughter of Joseph Morrill) in memory of her husband, Dr. James E. Lothrop. The land was donated by Hattie J. Bickford. Lothrop Hall was built in 1916.

Lothrop Hall

The cornerstone contains a box with building plans, articles and photographs of the Lothrops. The St. George Maronite Society was founded by the Lebanese people living in Dover on April 4, 1938. Michael Nadeau was the first president. They decided that each member should pay $1.00 per month to raise money for a church. In 1945, they purchased this building and it has been used for services ever since that time.

This historical essay is provided free to all readers as an educational service. It may not be reproduced on any website, list, bulletin board, or in print without the permission of the Dover Public Library. Links to the Dover Public Library homepage or a specific article's URL are permissible.