Disclaimer

The Dover Public Library website offers public access to a wide range of information, including historical materials that are products of their particular times, and may contain values, language or stereotypes that would now be deemed insensitive, inappropriate or factually inaccurate. However, these records reflect the shared attitudes and values of the community from which they were collected and thus constitute an important social record.

The materials contained in the collection do not represent the opinions of the City of Dover, or the Dover Public Library.

1988 Heritage Walking Tour

Heritage Walking Tour Booklet June 1988 by the Dover Heritage Group, Dover, NH, c. 1988.

In 1978, a group called Dover Tomorrow formed to promote the growth and prosperity of Dover. A subcommittee was tasked with promoting “appreciation of Dover’s heritage”. The Lively City Committee created the first Heritage Walk the next year. It was so popular that new tours were created every year, and held through 2007. By 1982, Dover’s historical society, the Northam Colonists, had taken over the research and creation of the Heritage Walking Tour Booklets. The information on the page below is a transcription of the original Heritage Walking Tour Booklet. The Library has a complete set of the Heritage Walking Tours if you would like to see the original booklets.

The Bellamy River

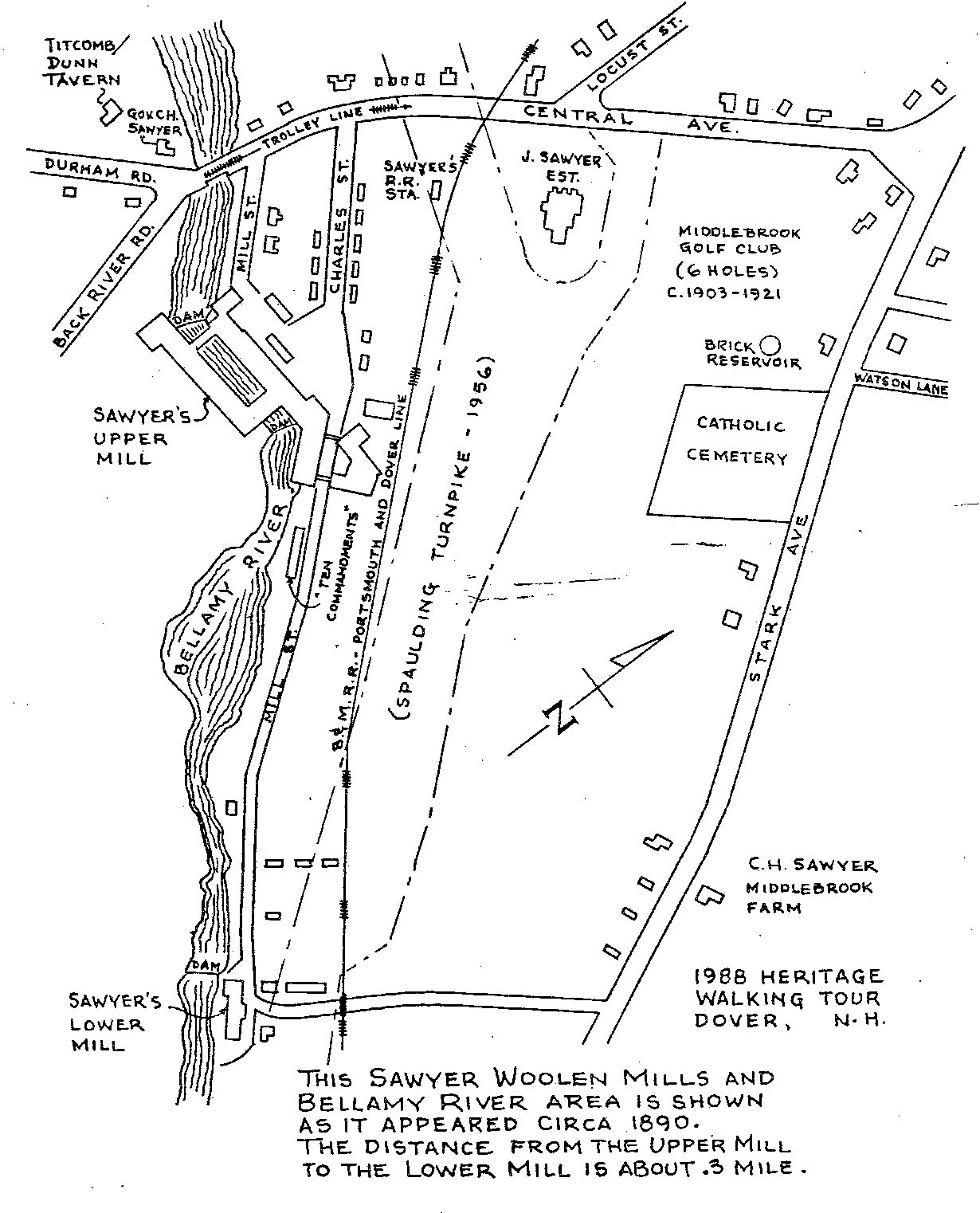

Flowing from Swain’s Pond in Barrington, through Madbury to the Lower Mill at Sawyer’s, and encompassing thirteen falls along its way, the Bellamy River joins Back River at the Lower Mill’s First falls. The river then parallels the Spaulding Turnpike for four miles, splitting Dover’s south side into two halves, finally flowing into Little Bay at Route 4’s Scammel Bridge.

The origin of the name “Bellamy” is unclear, with two theories prevailing; one holds that the river was name for a servant of a farmer William Bellew (Bellew’s Man). Bellew was a landowner with twenty acres of land on the north side of the First Falls in 1644. The second opinion credits the name to an Indian named Sagamore who had a cornfield here in the 1640s. It seems the Indian was so fat he was nicknamed the “Belly-man” and the stream became known as Bellyman’s Bank by 1646.

In any case, the many falls of the Bellamy River were seen as great sources of water power to run mill machinery. As early as 1650, sawmills and gristmills existed here, and over the next three centuries dozens of small industries thrived on these waters. The types of factories included an iron foundry, flannel, cotton, and woolen mills, cloth dressing and carding mills, yarn manufacturing, nail and knife factories, a machinery shop, a brewery, a hosiery factory and a sewing machine manufacturer, a bone grinding mill, a shuttle and axe handle factory, color shops and bleacheries, a railroad box car factory, sash, blind, and door manufacturers, clapboard mills, a shingle, cob, and lathe maker, and a cider mill. During their heyday in the 1840s, the yarn and cloth manufacturers would pay women workers 50 cents a week plus board for producing 40-60 skeins, or $1.00 a week for weaving 30-50 yards of fabric at home on a hand loom.

On close inspection, several of the old mill sites’ foundations can still be found near the various falls of the Bellamy. For further exploration, a complete history of each falls and its industries can be found in John Ham’s paper, “Back River and Bellamy River” (ca. 1890) available at the Dover Public Library.

In the twentieth century, the Bellamy River became the site of a park at the Fifth Falls. During 1936, the Civilian Conservation Corps built a bathhouse, sandy beach, diving platform, and footpaths, and Bellamy State Park was opened adjacent to Bellamy Road. For several decades the park served as a popular Dover recreational site, but it eventually closed in1974 due to vandalism and a high bacteria count in the water.

Sawyer Woolen Mills 1824-1899

The first mill on the Bellamy River at this site was a sawmill ca. 1649, owned by Major Waldron. The major gave one-quarter of his land here to his son-in-law John Gerrish who started a grist mill at the Third Falls after 1668. The land next passed to Gerrish’s son Timothy who operated a sawmill here in 1719. In 1760, this factory was converted back to a grist mill and by 1800 the mill was owned by Benjamin Libbey.

Around 1821—22 the rights to the Third Falls came into the ownership of Isaac Wendell (a man instrumental in establishing industry on the Cocheco River also). Wendell additionally purchased an iron foundry at the First Falls which had been in operation since 1817. He shortly sold both these rights to the Great Falls Manufacturing Company. Great Falls also purchased Second Falls privileges during 1824.

Mill privileges at the Third Falls were then leased to an enterprising young newcomer to Dover, Alfred I. Sawyer of Marlborough, Mass. Sawyer had been in town about a year and saw great potential for cloth manufacturing on the Bellamy. He built a new two-story wooden mill on the site of Libbey’s mill, had a new dam constructed there by builder William Drew and began to dress cloth in the small factory. In 1825, Sawyer added carding machines to the mill and the following year purchased the rights to operate a grist mill on the Second Falls. He began manufacturing flannels with one set of machinery; in 1837 a second set was added. So by the time of his death in 1849, the cloth dressing, carding, and flannel manufacturing businesses established 25 years earlier by Alfred I. Sawyer were thriving, profit-making operations on the two falls below Libbey’s bridge. The businesses passed to Alfred’s three brothers, Zenas (who retired in 1852), Francis A. of Boston, and Jonathan, who was only 32.

Jonathan Sawyer was even more of an entrepreneur than his eldest brother. In 1853, he was the first factory owner to use gas for lights; in 1858 he purchased the Lower Mill at the First Falls with two sets of machinery: by 1860 that mill contained four sets, by 1863 eight sets, and by 1882 sixteen sets.

In 1863, Jonathan and Francis Sawyer had Swain’s Pond in Barrington (the headwater of the Bellamy) enlarged in order to serve as a reservoir for their mills. The next year, a round brick reservoir, eight bricks thick and eighteen feet high constructed on the hill adjacent to the mills to hold water not only for manufacturing purposes, but also to supply Jonathan’s new 26-room mansion on Linden Street with plumbing facilities and an artificial pond. (The 1864 round reservoir is now a private residence on Birchwood Place.)

During the Civil War, Sawyer Mills machinery was gradually converted from flannel production to woolen manufacturing. Soldiers uniforms for the Union Army and N.H. regiments were made here in Dover at that time.

In what was described as a “bold innovation,” the Sawyer brothers chose, in 1866, to sell their finished goods directly to retailers, bypassing consignment shipments to commission houses. Their business savvy of elimination the middle-man met with “great opposition but…their foresight overcame all; they made a success of it” producing “fine fancy cassimere’s, cloths, and suiting’s.”

By the early 1870s, the company was booming: extensive renovations were made to both the Upper and Lower Mills. At the Upper site, the flannel mill at the Second Falls was taken down and a new, larger, brick mill with all new machinery was built in its place. At the Lower Mill, new machinery was added to the brick structure which had been constructed in 1845 by C.C.P. Moses. Moses had originally used the Lower Mill for paper manufacturing but had switched to flannels in 1855. The Lower Mill had been purchased by Sawyers in 1858.

Jonathan’s eldest son, Charles H. Sawyer, was admitted to the company as Superintendent and the business was incorporated as Sawyer Woolen Mills in 1873 with capital of $600,000. At this time, the factories had twenty sets of machinery manufacturing 900, 000 yards of wool each year and 300 employees. In 1876 at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, judges awarded a medal and diploma to the Sawyers’ goods for “high intrinsic merit.”

Also during the 1870s, the Sawyers built fifty tenements: in the area to house the company’s workers. These included the double houses on New Street (now Charles St., renamed in 1890 for Charles H. Sawyer.) and the Ten Commandments on Mill Street. Dan Smith of Dover wrote: “Sawyer’s Village was a happy place with a railroad station and a social life of its own. If you weren’t a Southender you didn’t belong--- bonfires, band concerts, fireworks, celebrations.” The company continued to grow in the 1880s. After Francis’ death in 1881, Charles H. Sawyer became Agent and the mills continued to expand. Swain’s Pond, the reservoir for the mills, was enlarged again to 450 acres. This action caused the water level to rise six feet, eliminating the need for using steam power at the Lower Mill in the summertime. By controlling the flow of the Bellamy, the overseers could rely entirely on water power even during the dry season.

Many new buildings and additions (many with sprinklers and full fire apparatus) were also constructed during the 80s: a bigger dye house, a repair shop, coal house, stables, four three-story extensions to the Upper Mill, three brick storehouses, and the Counting Room (Paymaster’s) building (the latter fully restored by the Kane Company). Sawyer Woolen Mills in 1884 boasted thirty sets of machinery consuming 2,400,000 pounds of wool annually, and 450 employees. Raw materials and finished goods were brought in and out by railroads cars to Sawyer’s Station adjacent to the mill or by mid-size sloops and barges which could navigate at high tide up Back River to the Lower Mill.

In a brief respite from his company management job, Charles Sawyer, then age 47, took time off in 1887 to run as the Republican candidate for governor of New Hampshire. He won the election and served a two-year term until 1889. The Dover Daily Republican extolled him as “a man of superior business capacity, kindhearted, generous; …a temperance man with a keen sense of justice … popular with his employees… never any difficulty with the help; no strikes or lock-outs or shut-downs have occurred…”

After his terms as governor, Charles returned to Dover and to the company. His father Jonathan died in 1891 and Charles became president and installed his sons as officers: William as treasurer, Charles F. as Superintendent. Machinery for the manufacture of worsted yarn also installed.

In May, 1899, The Sawyer Woolen Mills were purchased, along with many other privately held mills in New England, by the American Woolen Company of New York. Gov. Charles retired but his sons continued working for the new conglomerate until 1907. The last of the Sawyers were gone, but the two factories in Dover continued to flourish. Manager A.B. Paton said in 1916: “Woolens are second in importance to cotton manufacturing as the industry of New England, far exceeding the boot and shoe industry.” The American Woolen Company Dover branch now had 550 employees and forty sets of machinery.

But following the Depression, the industry slowly cut back. Only thirty-two sets of machinery operated in Dover following 1929 and the Lower Mill was sold during the 1930s. Work at Sawyer’s Upper Mill continued for the next three decades, with manufacturing operations terminated about 1954.

Since that time, neither mill has stood idle. The Lower Mill has served as the site for the production of many diverse products over the last fifty year including toys and games, Christmas tree ornaments, camera and film, paint, ice creepers for the Russian troops during World War II, rifle grenades, ski poles, waterproof boxes, and wooden shoes. Two Louis de Rochemont motion pictures were filmed at the Lower Mill site in 1951 and 1952: “Whistle at Eaton Falls” starring Lloyd Bridges, Dorothy Gish and Ernest Borgnine in a film about a strike at a small plastics factory, and “Walk East on Beacon” with George Murphy as an FBI agent on the track of communist spies in the U.S.! Currently, the Lower Mills is used by Holmwood Decorating Center for the manufacture of their unfinished wooden furniture.

At the Upper Mill, a retail store, the Sawyer Mills Factory Outlet, opened in 1956 and a grocery store was soon added. The Outlet closed in 1981, the supermarket one year later. In 1983, the 241,000 square foot mill was sold and the redevelopment of the Sawyer Mills as apartments was begun. The converted complex opened in 1986 and currently offers 188 studio, one-bedroom, and two-bedroom rental units.

Sawyer Mansion Site 47 Central Avenue (now Burger King)

Once the home of Sawyer Woolen Mills magnate Jonathan Sawyer, this 26-room Italianate mansion was built on this site (then called Linden Street) during the Civil War at a cost of $250,000. A five-story front tower was added in 1885. Jonathan, his wife Martha (Perkins), and their seven children lived in the magnificent house here which included a 40 X 19-foot drawing room and twelve-foot ceilings frescoed with gold leaf; the family played on the sumptuous 17-acre grounds complete with stable, carriage house, cold cellar, fruit orchards, greenhouse full of foreign and exotic plants, and an artificial pond supplied with water from the mill reservoir.

Jonathan died in 1891, Martha in 1896 and the house was sold to Charles G. Foster, publisher of the local weekly newspaper. By 1916, the home was sale again: an ad in Foster’s Democrat offered the house with seven acres at a price “a small fraction of the original cost.”

During the 1920s, the mansion was owned for a time by Hollywood producer and choreographer Busby Berkeley who was directing several New England summer stock theater companies. But the property was eventually taken over by the city after Mr. Berkeley neglected to pay his taxes.

The house was vacant during the 1930s, but was sold at auction in 1943 to John Soteropoulous. In 1954, the State of New Hampshire gained control of the property through eminent domain in preparation for construction of the new Spaulding Turnpike. It was torn down in 1958 when the overpass was built. A large picture of the Sawyer Mansion still hangs in Burger King Restaurant.

Middlebrooke Golf Club Ca. 1903—1921

Dover’s first golf course was located on several acres now occupied by Birchwood Place and the entrance to the Spaulding Turnpike adjacent to Burger King. The club was organized about 1903 and the 1607-yard golf course had but six holes, the longest a 410-yard par 5! Golfers had to not only play around the Sawyer Mills brick water reservoir, but also had to avoid the cow patties left by the grazing herds of Middle brook farm. Caddies were often hired just to retrieve golf balls from nasty lies on the course.

Middle brook Golf Club also had a small clubhouse (now moved to 58 Rutland Street) and a tennis court. Dues were $5.00 per year, with ladies offered non-noting associate memberships for $2.50.

In 1921, the club reorganized as the Cocheco Country Club and moved to larger facilities on Gulf Road.

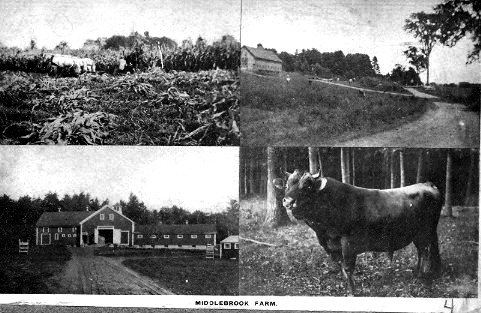

Middlebrook Farm 90 Stark Avenue

The large white colonial home on Stark Avenue was named Middlebrook Farm about 1900 when Governor Charles H. Sawyer and his family retired there. Originally built in 1780 by farmer Caleb Hodgdon who owned several hundred acres of land in this area, the farm was inherited by Gov. Sawyer’s wife, the former Susan Cowan (Caleb’s great-granddaughter). Charles Sawyer had served as president of the Sawyer Woolen Mills since 1891 but had sold the company in 1899. The farm, which extended from Watson Lane to the present location of Hoppy’s Store and back to Middle Road, seemed an ideal estate for a retired magnate and former N.H. governor. The Sawyers had lived previously at 2 Central Avenue (between Dunn’s Tavern and the Bellamy River: house torn down ca. 1967) but having no further reason to live so close to the mills, moved happily to Stark Avenue to start a dairy.

Middlebrook Farm was a large supplier of the county’s milk during the early 1900s. After Charles’ death in 1908 and under the guidance of his daughter Elizabeth, the farm was well managed and prided itself on using the most scientific methods of feeding and production. During the mid-1940s, bovine disease struck the herd and all the cows had to be destroyed. By 1948, the estate became Green Pastures Rest Home. It is currently an apartment house.

Dunn’s Tavern Durham Road

This colonial house is well over 200 years old. In 1780 it was operated as a tavern by Col. Benjamin Titcomb (1743—1799), a Revolutionary war veteran wounded in three battles. A selectman in Dover in 1781, Titcomb owned all the land on what is now Charles Street and the turnpike entrance on Central Avenue. Titcomb’s sister, Ann (1735—ca. 1815) married Benjamin Libbey (1737—1821) who operated the grist mill at the Third Falls of the Bellamy. The bridge there was called Libbey’s bridge.

In 1820, Captain Samuel Dunn (1766—1850) bought the tavern and the bridge became to be known as Dunn’s bridge. In 1825 Dover dignitaries gathered here to pay tribute to General Lafayette who was touring New Hampshire. As the general entered from Durham, a thirteen-gun salute was fired from atop Pine Hill to the assembly at the tavern.

The tavern continued operations through the 1840s and the home remained in the Dunn family until Miss Eliza Dunn’s death at the age of 80 in 1898. By 1899 the house had been converted to tenement housing for the workers at Sawyer Mills. The house is presently unoccupied due to pending litigation concerning its ownership. (The house has since been torn down in 2013.)

Also at this site on the Bellamy River bridge was the starting point of the Dover Horse Railroad Company which in 1882 began running trolley cars pulled by 14-horse teams on a 2.39 mile route to Garrison Hill. In 1892, the tracks were electrified and the route expanded to Burgett Park in Somersworth.

On the opposite side of Dunn’s Tavern, heading toward Durham on what is now Route 108, were Dunn’s woods, a reputedly haunted area: “the scene of many robbery by day and supernatural occurrences by night!” Historian Mary Thompson in 1892 credited the ghost stories to the strange “phosphorescent light which on dark nights were seen gleaming here and there among the bogs and decayed woods.”

This historical essay is provided free to all readers as an educational service. It may not be reproduced on any website, list, bulletin board, or in print without the permission of the Dover Public Library. Links to the Dover Public Library homepage or a specific article's URL are permissible.